I am resting on a marble step inside St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. Next to me rises a huge pink and white marble column.

From my perch at the foot of this column, I can see much of the ceiling stretching down the nave—the long central aisle of the church. Earlier, our guide explained how the shape of this church came to be. Originally, the architect Bramante intended for St. Peter’s to follow the design of a Greek cross, in which all four arms are of equal length. But Michelangelo, working under different pressures, modified the plan into a Latin cross, with the nave longer than the side aisles—symbolic, of course, of the crucifixion. Later architects extended the nave even further. It now stretches the length of more than two football fields.

(You can’t see the side aisles from this vantage point, but you can get an idea of how long the church is and how full of people it is.)

Rick Steves captures the architectural tension well:

“Michelangelo was a Renaissance man in Counter-Reformation times. The Church, struggling against Protestants and its own corruption, opted for a plan designed to impress the world with its grandeur—the Latin cross of the Crucifixion, with its nave extended to accommodate the grand religious spectacles of the Baroque period.”

(Rick Steves: Rome, 23rd ed., 2022, p. 248)

All around me, crowds of people move constantly, most with cameras at the ready, many wearing earbuds connected to whisper-light devices (they help you hear your group’s guide better). Our group has turned in our headsets; the tour is over. We’re on our own now.

(Here you can see one of the side aisles of the shape of the cross… and the many people milling about.)

We began the day walking through the Vatican Museums. I was struck by the representations of Roman gods and goddesses scattered throughout the Pope’s collection. Though beautiful and rich with story, they felt oddly out of place—dislocated images of glory no longer worshiped, set now within the trappings of another faith.

(From Roman mythology, in the Vatican Museum.)

Then came the Sistine Chapel. No photos are allowed. It is both more crowded and more alive than I expected. The ceiling is filled with motion—bodies writhing, reaching, twisting in painted narrative. Below, hundreds of real bodies move restlessly, craning necks, whispering reverently, snapping illicit glances upward. The ceiling panels tell the story of creation and the birth of humanity. Yet all that depth is an illusion. It’s trompe-l’œil—a masterful trick of the eye, painting depth where there is none.

The Last Judgment covers the far wall. The color blue stands out to me. The tangle of saved and damned souls is disturbing in its chaos. On the viewer’s right (Jesus’s left), the condemned descend. Michelangelo painted his own face into the flayed skin of one soul on that side. Perhaps he wonders what will happen to him on Judgment Day?

(This image is from the Wikipedia article: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sistine_Chapel_ceiling)

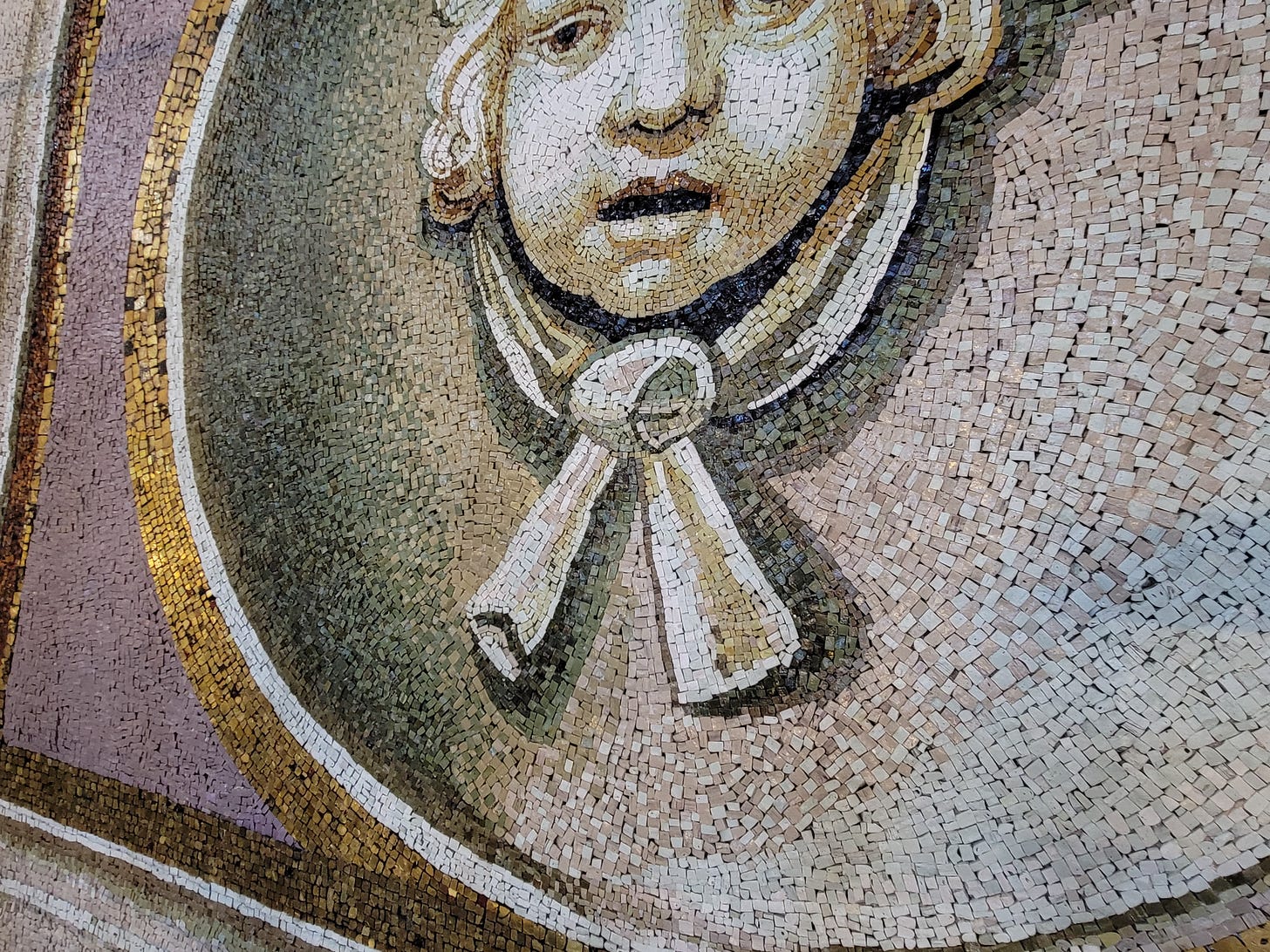

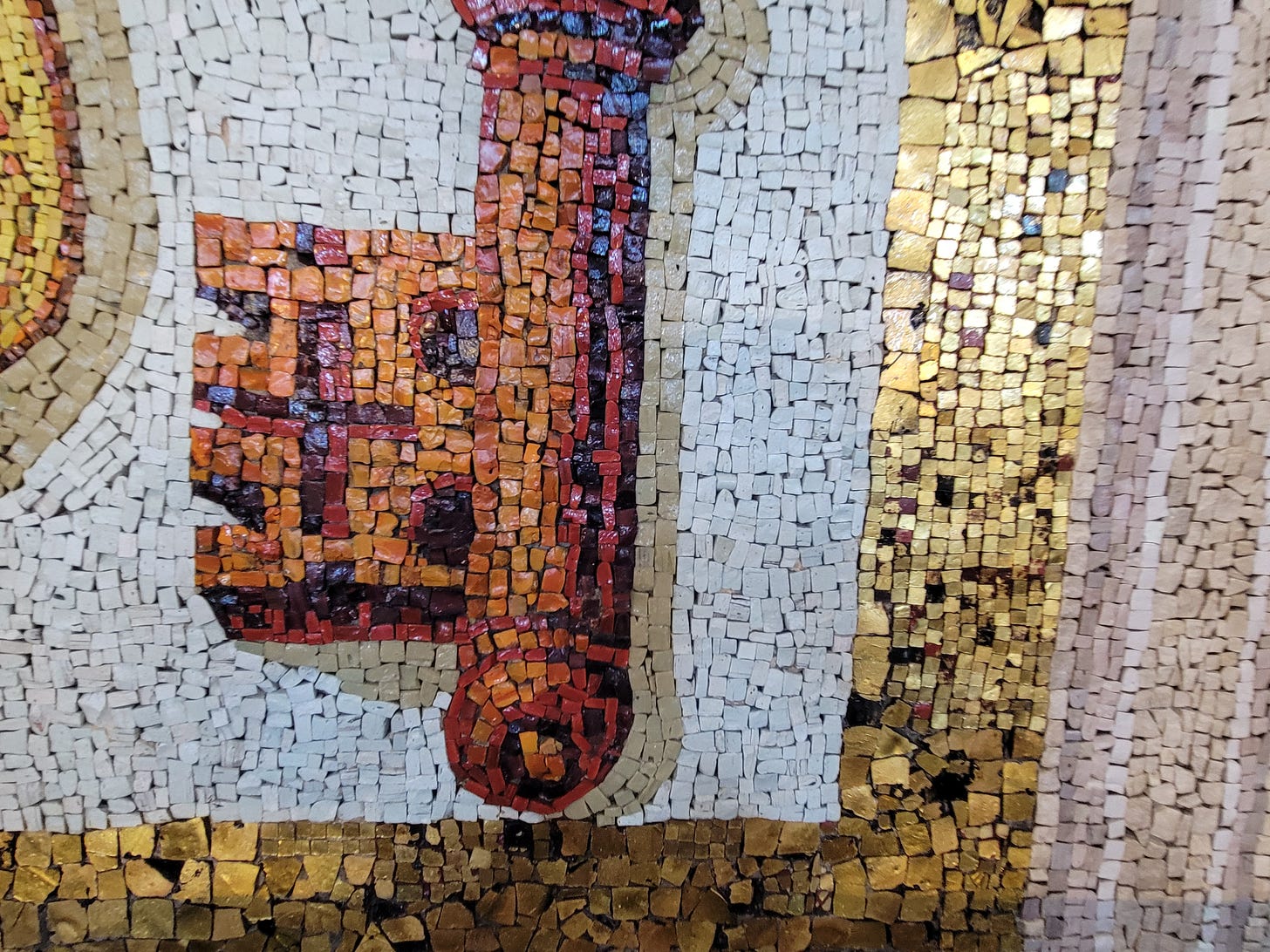

Now, I rest inside the basilica itself. There are no paintings here, only mosaics. Every image, no matter how lifelike from a distance, is formed from tiny fragments. They are stunning. Yet even as I sit, I notice: though my body is at rest, the visual noise never stops. Gold, sculpture, color, ornament; my eyes and mind can find no quiet.

Then, after moving slowly in another line, I do find quiet… of a sort. I come face-to-face with Michelangelo’s Pieta. I won’t tell you what to think about this indescribable work of art. I encourage you to spend a few minutes taking it all in for yourself. The folds of the clothing; Mary’s face and hands; the limp body of her Son, our Savior. The fact that because it is made out of white marble, it is unrealistically bloodless.

As you sit with it, what else does God say to you through this image?

A mass begins in the front of the nave beneath Bernini’s sculpture. The organ begins to play, which delights me.

(I used to think this was much too ornate for my taste. But a couple of years ago, I gave our children Christmas ornaments that matched major rose windows from significant churches around the world. After they all selected their favorites, there was one left for me: this image of the dove flying out of the sunburst. [Or is the dove bursting out of the sun? I’m not sure.] I’d forgotten where the original was located when I hung it in the window by my desk. Now, when I look at it, I’ll feel like God is speaking to me, reminding me that He’s always ready to burst onto the scene of my life.)

Amid the swirl of people, I imagine Jesus in the temple courts during the final week of his life. The Temple, too, was a grand space filled with people; religious tourists, faithful pilgrims, curious observers, each one following their own itinerary. The noise, the movement, the layered significance. I imagine Jesus, not rising above it, but walking through it. God incarnate, moving within a distracted crowd. Speaking softly amid the whispers. Offering truth amid a sea of individual commentary.

That image—the Christ who walks among us—brings me to another realization.

I’ve watched the masses of tourists here, each one focused on their own goal: snapping a perfect photo, listening to their guide, staying with the group. I realize: I’m doing the same things.

How often we move through life like this, surrounded by beauty and mystery, yet absorbed in our own plans. We are each fragments of humanity, jostling past one another, forgetting that we form something much larger than ourselves. Like the mosaics that fill this cathedral, we are individual pieces of a divine image. When placed by the hands of the Master Artist, our lives together tell a story of glory.

(I climbed over 500 steps to get first, to the balcony in the dome where I could look down onto the floor of the church below, and then outside to the ledge overlooking the city in 360 degrees. From below, these look like paintings. From the balcony, you can touch them and see the individual pieces placed side by side to create a complete picture. Every single piece is critical and plays its part in completing the whole.)

(Viewing the floor below through the plexiglass.)

But there's a more sobering analogy too: like the trompe-l’œil ceiling, we often live by illusions of depth. We wear the appearance of spiritual life—sound bites, schedules, even sacred language—but beneath it, our souls may be flat and restless. Jesus invites us to exchange illusion for intimacy. He calls us to restore us.

And maybe, just maybe, the fact that I could sense these analogies only after sitting down is its own lesson. Sometimes, it’s not until we sit still, in the noise of the world, that the Spirit gently reveals what was just under the surface all along.

And here’s the truest part of it: none of us is meant to see the whole picture on our own. We were never meant to walk through sacred spaces—or life itself—as isolated individuals snapping our own, unrelated personal images. We are fragments, yes. But when placed by the hands of the Master Artist, our scattered pieces form a picture far greater than we could imagine. Together, we are the mosaic. Together, we become the masterpiece.

Reflection Questions

Where in your life do you feel like part of a crowd—moving, producing, reacting—without fully noticing the sacred around you?

What “whisper-guides” are shaping your attention these days? Are they helping you hear God more clearly, or are they maybe hiding God’s voice and invitation?

Are there places in your spiritual life that look deep, but are more illusion than substance right now?

What would it look like for you to pause long enough for God to show you what’s been just beneath the surface?

How might you begin to see others, not as distractions or obstacles, but as tiles in the same divine mosaic of which you’re a part?

Thank you for sharing your observations and insights while visiting Rome. You pose some deep and profound questions. Much to ponder!